- What is tea?

- Where did tea come from?

- The Types of Tea

- Flavored vs Unflavored

- What Makes a Good Cup?

- Okay, But How Do I Make It?

- So, What Else?

So you want to know more about tea and why I’m so into it that I’d write a blog on it. There is of course more detail in tea than could be put into one blog post and stay readable. But I will give a crash course for you to dip your pinkey into the mug.

What is tea?

This is a tricky question to answer. Are we talking about the leaves used in making the beverage, or the beverage itself?

What are Tea Leaves?

If we are talking leaves, the scientific designation belongs solely to leaves from the plant known as Camellia Sinensis. This plant is native to the south eastern regions of Asia, but can be found growing in many other places thanks to the genius of tea-loving green-thumbs. If you use leaves, buds, flowers, or anything else that isn’t from this plant it is usually referred to as a Tisane. It’s French for “non-tea”. Really imaginative I know, but sometimes you might see “herbal infusion” or herbal tea”.

Tea as a Beverage

That then lands us to how people use the word “tea” when describing the beverage. Tea as a beverage usually refers to any kind of leaf steeped in water. English is a funny language and people like definitions to be simple. And I wont knock the use either. Shared language helps us share the things we love.

In my days as a tea shop employee the distinction was important because we were educating people about tea and specifics are important. Also having a set of options on the shelf that are (almost) all caffeine-free is huge for people who are avoiding it.

But as I have stated several time, I am only a snob for myself. But you did come for an education on “tea” and so welcome to deciding whether or not to correct people when it comes up now.

Where did tea come from?

Current records show China as the birthplace of our favored leaves. In classic Chinese fashion there is a myth told about an emperor accidentally getting some leaves in his cup and drinking it. What probably actually happened is people started by eating the leaves for energy.

This led to tea leaves becoming medicine that they would chew on for energy. I try to imagine eating the leaves straight and its rough. From there some people decided to put it through a grinding process and then adding water for ease of consuming it. Those of you keeping score will note that means powdered tea started in China before becoming refined in Japan.

Speaking of refined, much later in Chinese History a man known as Yu Lu wrote a book known as “The Tea Classic“. A short book on his thoughts on how to properly refine, steep, and drink tea. This book gives a look into how tea was becoming more refined for the aristocracy at the time. Emphasis on aristocracy as he demanded 26 separate tea tools and only water that came from the mountain spring where the tea grew.

From there tea goes through a lot of changes and farmers experiment, usually by accident on how to create the different types of tea we now have. What are those? Glad you asked.

The Types of Tea

So when I use the word “type” of tea I am referring to the standard processing method that happens to the Camellia Sinensis leaf to become a certain style of tea.

There are 6 types of tea:

- White

- Green

- Yellow

- Oolong

- Black (Red in China)

- Dark (Black in China)

Again all these come from the same leaf, the difference is in what you do to the leaf to get your end product. I am going to do a very brief description of each.

White Tea

All tea goes through a plucking stage sometimes by hand and sometimes by machine plucking. White tea is usually taken and let dry sometimes in the sun sometimes inside or a mix of both. This keeps it fairly light as a tea as usually nothing heavier than that is done to it. Light, floral, sweet, and woodsy are common descriptors of white tea.

Green Tea

Green tea starts to take the steps further by adding some steps. Once the initial withering takes place you flash heat the leaves (de-enzyme) to stop oxidation keeping the green part of green tea. Add some shaping or rolling to the leaves to break the cells inside to get those wonderful polyphenols that give green tea it’s taste of fresh garden offerings. Green beans, spinach, sugar snap peas, umami broth, etc.

Yellow Tea

Yellow tea is a lesser known tea type that shares almost exactly the same steps as green, but with a pilled wrapping step before the final heating step to allow a maillard reaction that caramelizes some of the sugars in the tea giving a nutty, roasted, or floral note to its type. Its a more rare type because the wrapping/smothering step can only be done by being taught to know when to stop it by hand. It can’t be mechanized and less and less people know how to do it. A unique tea type that’s worth the hunt for green tea lovers

Oolong Tea

Oolong tea is in my opinion the most complex to categorize because of the various types that can be made. You have the addition of allowing partial oxidation to the leaves. The tired example in the tea world is a cut apple left out in open air starting to brown. The leaves do the same thing causing unqiue chemical reactions that change the flavor of the tea. You end up with multiple points where the maillard reaction can be stoped creating a host of oolongs ranging from more green to more black.

Black Tea (Red Tea)

Black Tea (Red Tea in China) takes the maillard reaction as far as the leaf will go, causing the dark colour we know in the leaves and the usual amber red colour in the cup. The shaping and drying are all part of this process but full length maillard browning is the key feature of Black Tea. This is known for having a fuller body, more astringency, darker deeper fruity or roasted flavors.

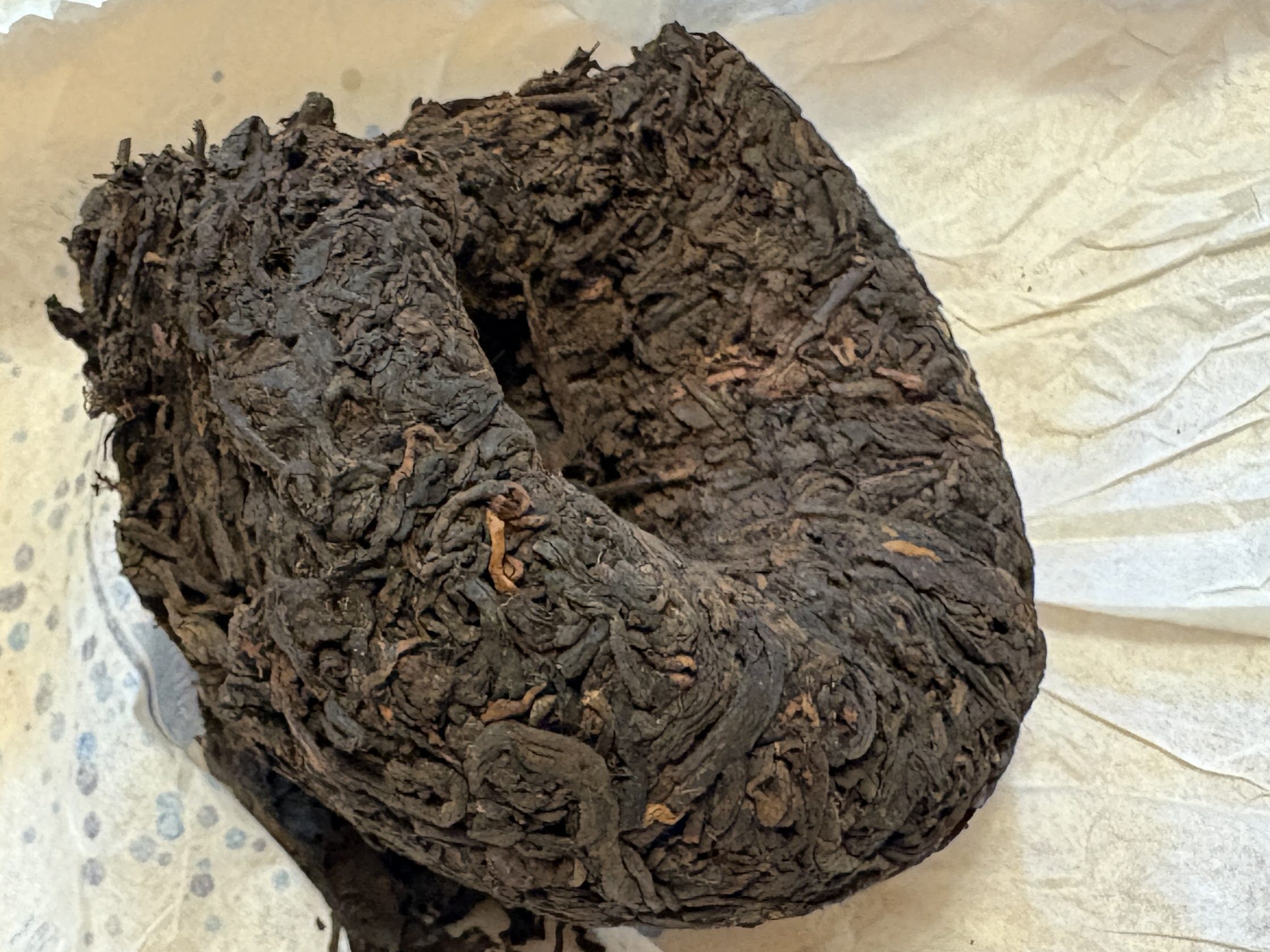

Dark Tea (Black Tea)

Dark Tea (Black Tea in China) is split into two categories: Raw and Ripe. These categories go with other names in China and Tea Enthusiasts, but for the sake of learning I think these names do the best informationally. Originally this tea comes from a village called Pu’er (pronounced poo-air……yes yes get your laughs out now) in the south of China. The village name became synonymous with the tea though other versions can be found from elsewhere these days and so only dark tea from Pu’er can be called as such.

Raw Tea

Raw dark tea was made through taking unfinished green tea, compressing it into a brick or cake and letting it ferment and age. This makes for some unique flavors that are close to green tea but with fermentation adding stone fruit notes or sometimes a more woodsy tone to the mix.

As mentioned, aging is part of the process and does change how the flavors come out, though good raw dark tea can be enjoyed from day one. But some of those cakes are on the market for a range of years and the older it is usually the higher in price. However it is a market saturated with some less than reputable claims. I recommend tasting what has high reviews instead of chasing an age statement.

Ripe Tea

Ripe dark tea came out of necessity. In the 1950s Hong Kong residents were holding dark tea in high demand and so a factory in Menghai developed a process that took wet leaves and piling them and turning them over. It’s a process very similar to composting. This would create a dark colour similar to very old raw dark tea but a flavor that was more earthy and full bodied. But didn’t require years of aging and so made a tea product that was able to be made quickly and sent to market.

So What About My Herbal Tea?

So as mentioned at the top, any plant material that you steep in water that isn’t from Camellia Sinensis, isn’t true tea. But that doesn’t mean it’s not good! Semantics in the tea world can make people feel like their favorite cup of Chamomile is “lesser-than”. This should not be the case.

There are so many wonderful brews to be made from the host of herbs and plants out there. Peppermint, Chocolate Mint, Chamomile, Hibiscus, Tulsi Basil, Catnip, dried fruits, dried nuts, Yaupon, and so much more. All of these have a home in your cup. There is a host of benefits to them, but aside from that, they are mostly without caffeine and for me that’s a huge boon at night.

The other beauty is you could grow these at home with little effort. Consistent shade, sun, and water, and you can harvest them all growing season. I have enjoyed drinking through our batches of mints, lemon balm, catnip, and more. I also have had fun blending them to create some nice brews.

So enjoy your herbs with no judgement from this writer!

Flavored vs Unflavored

This is one that ends up dividing a lot of tea lovers and confusing new drinkers. Unflavored tea is the leaf as it was processed and shaped without anything else being added to it. Flavored tea is taking the finished tea and adding something to it to get a specific flavor profile.

Flavored

The term “flavored” tea refers to something that wasn’t originally part of the leaf it self, is added to the tea to emphasize a specific flavor or set of flavors. An example is Earl Grey. Traditionally Earl Grey is black tea leaf with the oil of the bergamot fruit added to the leaf.

It is slightly more complicated than just dumping oil on the leaf, because it’s not really oil as we know it, see more come a colleague of mine who’s job it was to flavor tea for years. For the sake of today I’ll simply say oil but now we know better.

But this emphasizes what I mean. Black tea that wouldn’t normally have a citrusy note that specific suddenly has that note. Another example is teas with dried fruits or nuts added. The main idea is for the tea leaf to give more of a texture or mouthfeel than flavor and let the blended elements do that job.

Some wonderful teas come from this process. Sometimes the simple addition of herbs like Chamomile or Tulsi Basil give a unique tone to a black tea. Sometimes a more complex process lands you with a blend with grape and blueberry notes on a white tea that is a wonderful cold tea in the summer.

Flavored teas have a range of unique possibilities for many taste preferences.

Unflavored

Unflavored tea is just what the farm or factory did the the leaf (rolling, roasting, sun drying, etc.) and nothing else. This give a more subtle flavor profile to the tea but lets the chemical reactions from processing give a range of flavors.

Because of the above mentioned variations in processing the Camellia Sinensis leaf, you can end up with a range of beautiful profiles even in one category of tea. Some people spend many months trying multiple versions of one style of tea to get the minute differences.

This isn’t hard of course as there are many varieties in each type of tea. Take black tea as an example. In China alone you can find 8-10 major varieties just from one province. Much less jumping to other countries and regions. Like India. You can find black tea from Assam being more bold, malty and brisk. And then travel north west and find Darjeeling lighter, fruity, and woodsy. South of that you’ll find the Nilgiri region which lends a more stone fruit and citrus tone.

The allure of this comes in enjoying the craftmanship found in the tradition and innovation of seeing what flavor can be coaxed out of the leaf. For some, there is a joy in working to identify the flavor notes. Others enjoy the simplicity and subtleness in a unflavored tea.

Which is Better?

I have never like the term “unflavored” tea simply because it gives a false impression that unflavored tea has no flavor. A Dragonwell green tea has beautiful notes of fresh snow peas and crisp mineral water. A roasted Wuyi oolong has wonderful cherry notes along with its nutty roast. The list goes on.

The difference is of course these flavors are more subtle and can be very subjective from person to person. So someone who is used to highly flavored beverages won’t pick these up right away giving a sense of lesser-than compared to a blood orange flavored black tea.

But some purists in the “unflavored” camp start to look down on their Earl Grey companions as though the teas are not as high-quality as a prized Jin Jun Mei black tea. which leads to snobbery and as mentioned so many times in this blog, I am not about it and you can leave it at the door.

I confess to being less a fan of flavored tea because my pallet likes subtly and also some strange flavor notes like granite and wet earth which doesn’t come off as well if it was added as a flavor. But I enjoy Masala Chai especially as weather here in Alberta cools off. And I also like to add some peppermint leaf to my Pu’er for a lovely evening treat.

So as you delve into the world of tea, enjoy what you enjoy but don’t be afraid to branch out. You will find your tastes change over time and you enjoy new things and find the old standbys aren’t as solid for you anymore (though my Nepal Gold Tips will always be top of my list).

What Makes a Good Cup?

Tea gear. Such a large topic that it will need to be it’s own blog post later. But for the basics you have a few options worth getting into.

Basic Gear Options

-Infuser

-Teapot

-Favorite Mug

Infuser

If you want to go with loose leaf tea, you need what’s called an infuser of some kind. This looks like a basket with hold in it, or like a tall strainer. This allows the leaves to steep without needing your teeth as filters while drinking, though that is also a valid method according to some people.

The larger the infuser the better, within limits. This is because your leaves will open and expand as you make the tea and you want to make sure there is room to get all of the yummy flavor in your cup. Smaller infusers will constrict the leave giving you less.

Teapot

You can also get a teapot. These come in many shapes and sizes for all fashion “tastes”. Again, the more room for infusing the better. I prefer glass so I can watch the leaves and the color change but there’s a host of options. You can buy from your local tea dealer, but I’ll wager you can find a great option at your local thrift store as well. Some of my new favorites come from a thrift store.

Favorite Mug

You will also want a mug or a cup. I imagine your home is already filled with these and using your favorite is always recommended. But if you’re feeling all in on the learning experience, start hunting for a specific cup/mug for your tea experiments. It adds consistency to your tastings but also gives the experience something that is uniquely yours. No one else has the cup that you have and so adds to the ritual of making your tea.

Okay, But How Do I Make It?

So while there are ENDLESS way to make tea, there are two “standardized” ways that I think are good places to start. You have the western/teapot method of making tea and the eastern/gung fu method of tea.

Western

The western practice is pretty straight forward and is good if you want to make a cuppa and cozy up without much fuss. You take an infuser or teapot with good amount of room to it and add in your tea leaves. You could skip loose leaf and rock the tea bag as well. Again no judgement.

Get your water to the right temperature for your tea type. Pour water over leaves and steep for the right amount of time. Pull the bag or infuser out and add and extras you’d like or don’t and then cozy up with a book and sip.

Eastern

The eastern practice looks more involved at first, especially if you’re used to the western method but it does make for more in-depth tastings and steep times are much shorter, meaning drinking tea faster.

Originally you would use a Gawian, pictured below, to steep the leaves in and the lid is your filter for tea. However you can do this with an infuser, just paying attention to amount of leaf and volume of water. The idea here is more leaf, less water, less time, and multiple steeps.

This allows you to taste different more subtle flavors in the tea over many steeps. Getting a more in-depth appreciation of the tea. You also cannot do it quickly even though the steep times are less. The eastern steeping method lends to a more relaxed way of making the tea. Some use the time to meditate as they drink, other use it as a way to connect better with friends over a slower ritual of tea making.

What’s the Difference?

Western Steeping is great for flavored teas, people who want a simple way to steep, or teas that are designed for a longer single steep. Depending on the tea you may be able to resteep but more often than not the second steeping is lighter than the first. But its great for making individual cups for people quickly or a large pot for many guests.

Eastern steeping is best for people who want to slow down with tea, unflavored single-origin teas, tightly rolled leaves, people who want to expand their tea making processes. This process is great for “unflavored” leaves that are shaped and processed in a way that lend to multiple steepings or aged teas that take longer to coax out the flavors. Flavored teas don’t work as well with this method because they are designed to have a specific flavor or set of flavors that wont develop over time the same way.

Practical Instructions

Okay some of you reading are going “I need the numbers Sean. Where are my metrics?” I’ve got some good starting points though these are my measurements and not a standard as such:

Western Style:

3 grams of loose leaf tea for every 8 oz (230ml) of water.

White: 195°F (90°C) 3 Minutes or 175°F (80°C) 6-7 Minutes

Green: 175°F (80°C) 2-3 Minutes or 160°F (70°C) 1 Minute for Japanese Greens

Yellow: 175°F (80°C) 2-3 Minutes or 195°F (90°C) 3 Minutes

Oolong: 185°F (85°C) 3 minutes or 195°F (90°C) 3 Minutes

Black: 205°F (95°C) 4-5 Minutes

Dark: 185°F (85°C) 4 minutes for Raw or 205°F (95°C) 4-8 Minutes for Ripe

Tisane/Herbal: 195°F (90°C) 3-10 Minutes depending on the herb

Eastern Style:

The temperatures above generally are the same for starting with, though some people with the exception of green will go to boiling and let the coolness of the gaiwan or cup bring the temperature down enough.

1 gram for every fluid ounce (30 ml)

(Optional) perform a rinse by pouring just enough water to cover the leaves and pour off the water after a few seconds, but leaving the leaves in the vessel. This is good for more packed or tightly rolled teas

Start by steeping for 15-20 seconds and pour into your cup. Then for each steep add maybe 5-8 seconds per steep. Adjust time as your taste buds want.

Like I said. This is a good starting place for trying it out. You will find Your own way of steeping as time goes on.

So, What Else?

So much more. Differing techniques of steeping, intricacies of tasting with different temperatures, how different pot and cup materials effect flavor, and more. For today though, this should give you the building blocks to start, get comfortable, and then start branching out.

My itch for tea took off quite literally with a cup of hot black nameless tea on a British Airways flight on the way to India where I was then steeped in Chai for 6 weeks. So don’t feel you need to buy the fanciest, oldest, or rarest teas to get started. Try a simple cup of tea as close as you can find and then keep trying more after that; preferably with someone to share it with, but more on that in a later post.

Happy Steeping!

Leave a comment